I always felt special because I was born in Miami. My parents, like so many others, came from someplace else.

My father Jack Moore grew up in Waycross, Georgia and my mother Anne Parker in Maysville, Kentucky. My grandfather, John J. Moore, a lawyer and judge, moved to Florida during the great 1920s boom and settled in Stuart. My father moved to Miami as a young lawyer in 1930. It was at the height of the Great Depression. Times were tough he always reminded us

My mother came to Florida to attend Florida State College for Women, now FSU, in 1929. With the luck of the draw, she roomed with my father’s sister. She stayed only a year in Florida and graduated from the University of Kentucky and became an elementary school teacher there. During the summer of 1936, she visited her old roommate in Miami and at that time met my father. After a whirlwind romance, they married.

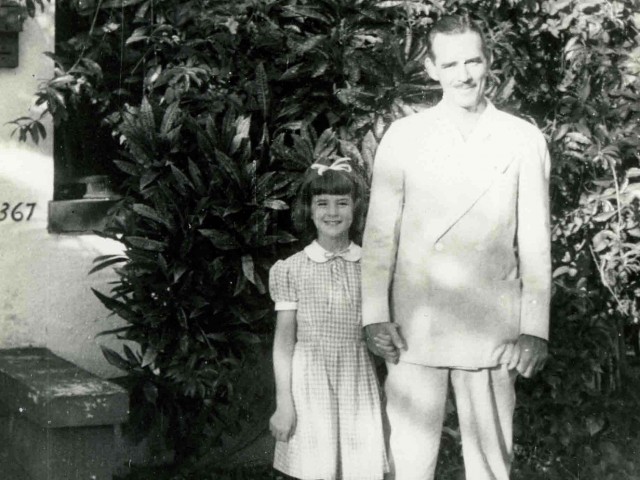

When I was born, the Moore family, which included my sister Pat and brother Bill, lived at 1367 SW Third St. in an area then called Riverside, now Little Havana. Our home was a wooden bungalow with a screened-in front porch. It was a perfect way to live before air conditioning. There were many children in the neighborhood and we spent most of our days outdoors — skating, biking and playing kick-the-can. I walked to Riverside Elementary and even came home for lunch.

We frequented two neighborhood shopping areas — one on Flagler Street and the other on what we called the Trail, now Calle Ocho. Every Saturday, my brother, sister and I walked to the Tower Theater to watch movies, cartoons, news reels and adventure serials. Twenty-five cents would buy admission, a drink and a bag of popcorn.

My family went to a downtown church so from my earliest years I was in downtown Miami at least once a week. As a result, I feel very much at home in downtown Miami, even today. There were four churches within walking distance of each other and their members frequently went to Luke’s Drug Store between Sunday school and church. Attending a downtown church made it possible to know people from all over Greater Miami. In high school, we even dated across town through friends we met in church youth groups. Because of these friends, I always saw Miami as a whole and not just as a sum of many parts.

When I was in the fourth grade we moved to Miami Shores. I thought we had moved to Jacksonville. Although this was considered an upward move for my family, I missed the old neighborhood and my friends. But I made new friends in Miami Shores, especially my best friend, Adele Khoury. We were the two tallest girls in the class and liked to call ourselves “back row” girls because we were always together on the back row in school pictures. We rode our bikes everywhere. We also went downtown on Bus 11 for a day at the movies and lunch at Royal Castle where hamburgers cost five cents. She remains my closest friend today.

I got my sense of history and my passion for Miami from my father. He always had his nose in a history book, taught me historical facts, a love for the constitution and took me around and told me things about Miami. “Remember this,” he would say. He ran for the City of Miami Commission when I was 5 and I remember passing out brochures at a rally in Bayfront Park. He and my mother set a good example by being involved in the community.

My family was ethnically Southern and I could talk and eat Southern-style. When it came to race, however, they were unlike most others who lived in then-segregated Miami. I was taught to respect everyone regardless of their race, religion, gender or ethnicity. My father often spoke out against segregation and anti-Semitism. Once, I remember being very embarrassed when he spoke out in a restaurant because the management would not admit black patrons. Years later, I realized how remarkable he was and how blessed I was to grow up in such an inclusive environment.

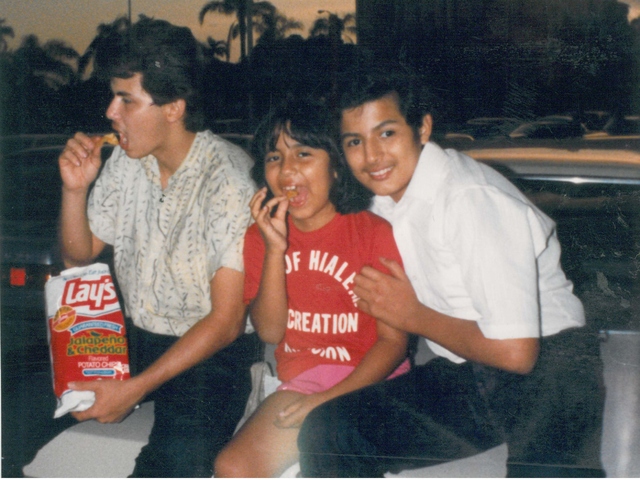

I went to college and my first career was an American history and government teacher. I taught at Miami Edison Senior High, my alma mater, the first year it was integrated. I also had a large group of young Cuban refugees in my class — many of whom had been sent to Miami without their parents. They taught me through example to respect the Cuban exiles who were moving to Miami. Many invited me to come visit them when they returned home to Cuba. Little did any of us realize that they would not be able to return for many years, if ever.

How lucky I was to be born and grow up in Miami.

Miami taught me to be open to change and to adapt to the unexpected. It taught me to accept people and welcome newcomers. It gave me an eagerness to learn. When I began writing Miami history and working to preserve its important places, I called on all these memories of people, places and events to help me. When I write about Miami, I always include everyone in the story. Each day, I realize more and more that there is no better place to live if you want a jump start on America’s future and always have a great story to tell.