I was raised in the Christian Science faith and went to church from the time I was 4 years old in 1939, but I always considered myself culturally Jewish. I had to go to school during the Jewish holidays as a kid in Brooklyn, and when classmates and teachers expressed surprise that I was at school, I responded: “I am a Christian Scientist of Jewish extraction.”

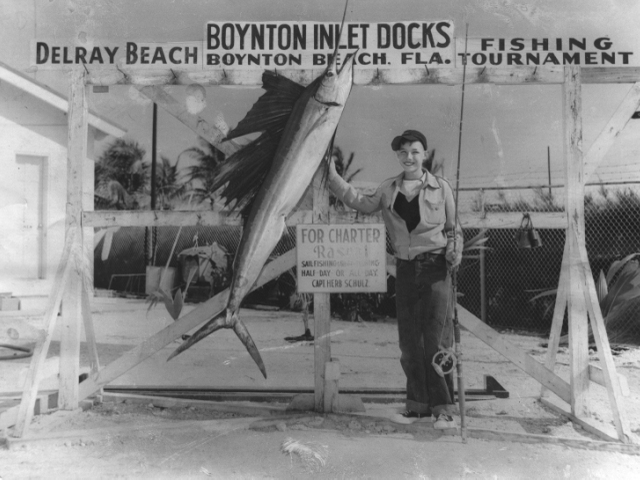

My parents, Paula and Louis Gelman, never denied their Jewish heritage to anyone, and many of my Christian Science friends in New York were also Jewish. I loved visiting my grandmother in Palm Beach as a child when my parents took me on vacation. Sadie Louber, my grandmother, owned a kosher hotel called the Louber Villa, at 231 Sunset Ave., a block and a half from the ocean.

Grandma Louber was a strong, loving influence in all our lives. My brother, Larry Gelman, says that Grandma took him to black churches in West Palm Beach because she loved gospel music, and Larry credits Grandma with his love of music to this day.

There were always interesting guests staying at the hotel. Grandma served kosher meals. My mother and her sisters were always very close, and it was fun getting together in Palm Beach with my cousins and their parents. There was never any discussion in my presence as a child or an adult about being Jews in a predominantly Gentile area, nor did I realize that it was highly unlikely that a Jewish hotel could have been owned by Jews in Palm Beach.

I moved to Miami as an adult in 1958. It was my first introduction to Miami Beach and its Jewish population and culture. During the early 1960s, we would visit Grandma at her hotel. We always got a kick out of the fact that the Kennedys had an estate in Palm Beach not far from where our family hotel was. To the best of my knowledge, we were still the only Jewish family owning property at that time in Palm Beach.

I decided to investigate how my family came to own this property. I asked a friend, real-estate attorney Daniel Doscher, to look into it, and he did the legal research on the property. He discovered that my father, who was an attorney in New York City, somehow managed to buy it in the late 1930s. He gave the title ownership to Paula Gelman, my mother, and her sister, Ruth Louber.

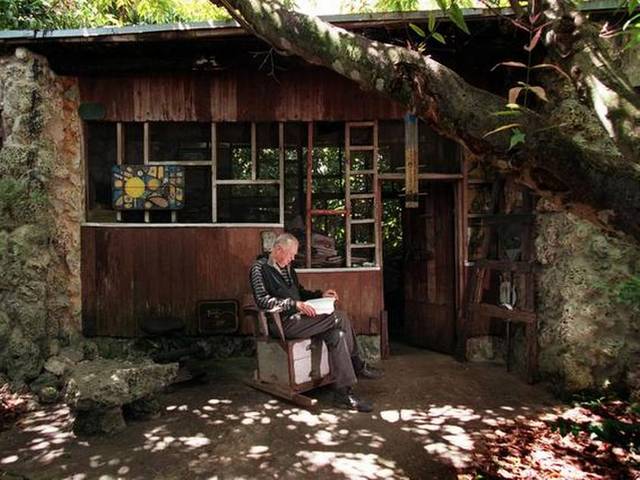

In 1945, the Louber Villa was transferred to Sadie Louber, my mother’s mother, and Grandma Louber took over the hotel. My grandparents had owned a hotel in Saratoga called the New Windsor Hotel, which they lost in the Great Depression of the 1930s. (I have no memory of Louis Louber, my grandfather, since he passed away when I was very young.)

A few years ago, I visited the Jewish Museum of Florida in Miami Beach and was shocked to see a sign in the museum collection that read: “Always a view, never a Jew.” I thought that the museum might be very interested in the story of the Louber Villa, a hotel that was Jewish-owned and that welcomed Jews in Palm Beach during those years. Today, the picture of the Louber Villa is now in the permanent collection of the Jewish Museum.

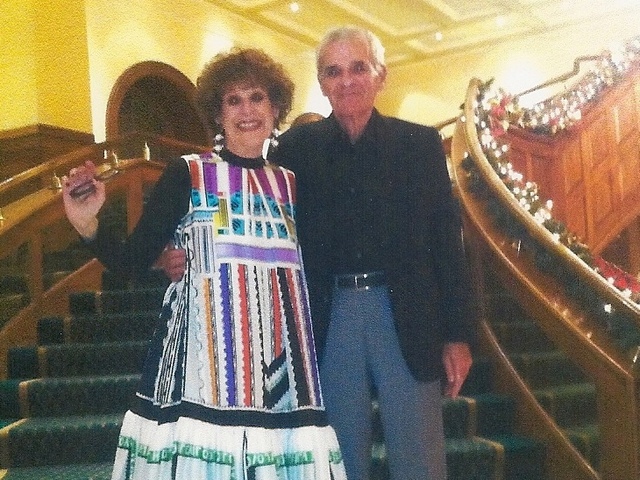

Even after the hotel was sold and torn down some years ago, we visited the empty lot annually and walked around the area for sentimental reasons. Recently, my cousin and her husband were in Palm Beach, and we got together there once again!

There is now a large, modern accounting firm on Grandma’s property. We walked to the corner of Sunset Avenue and County Road on our way to the beach, a block and a half away. Almost as a commentary on the inexorable passage of time, there is a beautiful Orthodox Jewish temple on the corner, barely two doors down from where our hotel had been.

Palm Beach has a special sentimental meaning for me, but my permanent home is now in Miami. The changes in the culture and population in South Florida over the many years I have lived here make me proud to live in Miami. It is an exciting place to call home.