Nostalgia. It is what happens to me when I start thinking about where Miami begins and where I end. This remarkable city, a nexus of comings and goings, is my homestead and refuge. Although young, I have enough “I remember when” statements to paint my childhood and youth with as much warmth as the offerings of Miami’s midday sun.

I remember when Sunset Place used to be the Bakery Centre, where inexpensive and fresh baked goods were actually sold, and which had a rare coin shop and an Eckerd’s Pharmacy on the side. Sunset Drive also had a children’s bookshop that had the most remarkable story hours that ignited my passion for reading. Saturday mornings were spent at Velvet Creme, the doughnut parlor that introduced me to crullers and provided my family and me a cozy place to start the weekend.

And how could I ever forget each hurricane? My first was Hurricane Andrew and ever since then, I keep track of Miami’s storms and their lasting effects based on the absence or damage of ficus trees in the neighborhoods. Each memory, even the ones on the surface, brings to life a part of my growing years here. These memories, vignettes really, represent the rich excess that defines my beloved city.

In the summer of 1996, my deliciously beautiful cousin Sohela came from the Netherlands to visit my family and me in Miami. This was a particularly special visit because it was her first time in Miami and my first time meeting her. I had high expectations because I had already bonded fiercely with her older sister, my cousin Sara, who in previous visits had convinced me that Sohela was a witch.

My two cousins, along with my precious mother, became model examples for me because they gave me a context for what it meant to be a modern Iranian woman. Sara and Sohela were beautiful, well-spoken, well-traveled and highly educated. Essentially, my two cousins represented everything my 12-year-old heart wanted to be when I grew up.

Having been born in Miami, and the only Iranian-American girl in my class, I often shied away from my olive skin, thick eyebrows and massive curly hair. I went by my middle name, Leslie, because it was much easier to pronounce than my first name, Saghar. I struggled with where I fit in Miami and more so, how I fit in my own skin. These cross-cultural family visits in Miami let me see the beauty of my heritage and appreciate my place in the broad spectrum of diversity in Miami.

When Sohela arrived, I was on the fence about her and used every outing to judge whether or not I was going to love her as much as I already loved Sara. When we went to swim and suntan at the Venetian Pool, where I first learned to swim, I decided to judge her by whether she could swim from the edge of one side of the pool to the cave on the other side of the pool without getting her sandwich wet. I stared her down in the cave, as we ate our perfectly dry sandwiches.

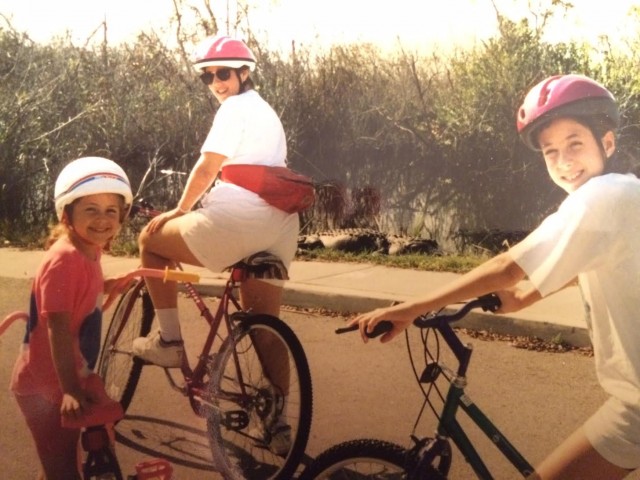

When we took her for early morning strolls at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, I quizzed her on starfruits, mangos, sabal palms and sausage trees. Would she appreciate the differences in our fruits and the different types of palm trees? At Matheson Hammock Park, I checked to see if she could spot the ridgeback of an alligator that was barely, just barely, skimming the top of the lake. Being the Miami girl that I was, I thought (and often still do) these things were important! One by one, Sohela passed my little Miami tests and with ease started to win me over.

The evening before Sohela left, we took her to South Beach. My parents, brother, Sohela and I all piled into our cream-colored Jeep and drove from our Coral Gables niche to South Beach. I watched her from the back seat taking in the sights from MacArthur Causeway. With the window lowered and her head slightly tilted out, I could see the light in her eyes as she took in the expanse of the port to our right, the beach in front, and the lights from downtown just behind us. More than anything else, I could sense she enjoyed the warm, evening breeze brushing her cheeks. As we inched our way to Ocean Boulevard, I wondered if she could hold her own in South Beach—outlandish, exotic South Beach.

We parked our car and started our stroll on Ocean Boulevard. Across the street, we heard a ruckus coming from the News Café. When we looked, we saw a row of five shirtless guys holding up large, poster score cards. As women would walk or drive by, they would rate them and hoot and holler. My heart was pounding because I wondered if they would rate Sohela and if they did, how she would fare. Holding my dad’s hand, I picked up the pace of our stride hoping that if we shuffled by quickly enough, we would go unnoticed.

What my cousin did next was so classically “Miami” that I fell in love with her forever. Sohela measured her steps and presented herself squarely in front of these men. She stretched her arms out and gave a slight bow. Sohela then slowly pivoted and awaited the reply. We stood beside her, my mom with a sassy smile and I, a bit bewildered. Sohela held court and the score cards revealed:

10! 10! 10! 10! 10!

In that moment, I soaked it all in. I remember the confident “I know!” nod my cousin gave, the rhythm of the beach, and the comforting hue of the evening sky. I started to wonder if, in that moment, there were any other place in the world as perfect as Miami for creating such an experience.

Years later, I still wonder.