AFRO-CUBAN ORISHA ARTS IN MIAMI

Yemojá, and Oshún.

Though Orisha artists are highly respected within the religious community, their work is not well known or understood by the wider public. This exhibition explores their creativity in the context of the aesthetics and symbolism of the centuries-old Orisha tradition. Access to a wealth of materials in Miami has enabled these artists to pursue strikingly original aesthetic visions, while still following traditional patterns and the fundamental precepts of the orishas.THE AFRO-CUBAN ORISHA RELIGION

ORISHA WORSHIP IN MIAMI

With the settlement of Cubans in the United States, particularly after the 1959 Revolution, the Orisha religion developed in New York, Miami, Chicago, and other cities. A series of mass migrations of Cubans to South Florida transformed Miami into the center of Cuban culture in America. The orishas accompanied their worshipers across the Florida Straits, just as they had joined earlier worshipers on the traumatic journey from West Africa to Cuba.

Cuban exiles to Miami.

The earliest wave of Cuban exiles to Miami consisted mainly of middle to upper class whites. For the most part, this sector of Cuban society was either alien to Afro-Cuban religions or consulted diviners only in times of crisis. The new stresses created by the exile experience in Miami led many people to turn to the Orisha religion, given its emphasis on practical solutions to everyday life and its extensive networks of mutual aid.

In 1980 close to 125,000 Cubans arrived in South Florida during what was known as the “Mariel boatlift.” This massive exodus included people from all strata of Cuban society, a significant number of whom were Orisha practitioners. The Mariel boatlift and more recent migration have played an important role in reinvigorating the Orisha community and its artistic traditions in Miami.

Over the years, people of many other cultural backgrounds have become Orisha practitioners. Though Orisha worship is now an integral part of the American religious landscape, it is still often misunderstood and subjected to negative stereotypes. Such misunderstandings are a legacy of years of colonial denigration of African cultural traditions.

ORISHA ARTISTS

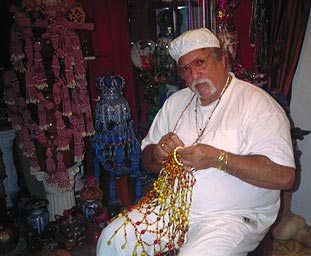

BEADWORK

PAÑOS

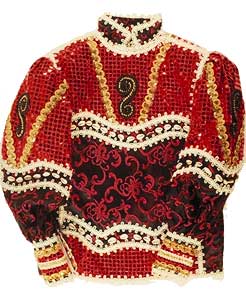

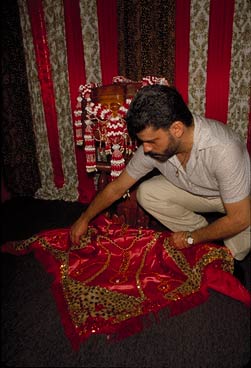

Paños (cloth panels) are used to “dress” orishas on special occasions, such as religious anniversaries or other spiritual celebrations. In past years in Cuba, many olorishas (priests/priestesses) embroidered their paños, though embroidered silk shawls, imported from Spain, were also quite popular. In Miami paños have developed into a particularly elaborate art form and generally are made by specialists, such as Jorge Ortega and Obdulia Garcia. Fine fabrics, beads, cowries, pearls, rhinestones, and metallic trimmings are all employed to create paños that reflect the colors, natural attributes, totemic animals, and emblems of specific orishas.

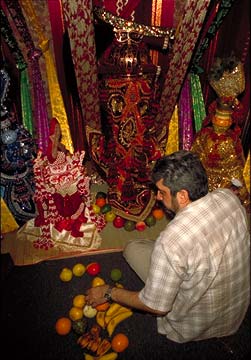

Paños are often used to adorn jars that contain ritual objects belonging to orishas. For the most part, their function is ornamental: they are meant to please an orisha and present him or her in an attractive fashion. At other times, the covering of an orisha is recommended by an oracle. Paños are also hung in thrones (altars), where they serve as flags of the orishas. During wemileres (drumming celebrations), paños are used to dress the orishas who possess olorishas. Typically, a female orisha wears a paño over her shoulders as a type of shawl, while a male orisha wears one tied around his waist. Frequently, orishas pass paños over the bodies of the attendees at a wemilere to cleanse them of any negative energy. Occasionally, an orisha may give a paño away as a present to a special devotee.GARMENTS

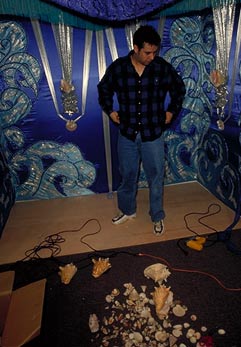

THRONES

HERRAMIENTAS

MUSIC

IFÁ PARAPHERNALIA

THE ORISHA TRADITION IN POPULAR ARTS

THE AFRO-CUBAN ORISHA PANTHEON

| Orisha | Domain | Colors |

|---|---|---|

| Elegbá | Crossroads | Red, black, white |

| Ogún | Iron, war | Black, green, Red |

| Oshosi | Hunting | Dark blue, amber |

| Osayín | Healing, herbs | No preference |

| Erinlé | Fishing, healing | Turquoise, green, coral |

| Orishaokó | Agriculture | Turquoise, mauve |

| Babaluaiyé | Smallpox, epidemics | Brown, black, red |

| Ibeji | Twins | White, red (sometimes blue) |

| Dadá and Bayani | Unborn children | Red, white |

| Iroko | Silk-cotton tree | Green, turquoise |

| Aganjú | Volcano | Brown, opal |

| Shangó | Thunder, fire | Red, white |

| Obatalá | Purity | White |

| Odúduwa | Death | White, opal |

| Oba | River | Brown, amber, coral |

| Yewá | Cemetery | Mauve, crimson |

| Oyá | Tempests, marketplace | Brown, red, burgundy |

| Yemojá | Ocean, all waters | Blue, opal, or crystal |

| Olokún | Ocean | Dark blue, red, coral, green |

| Nana Burukú | Lagoon | Black, mauve |

| Oshún | River | Amber, yellow, coral |

| Orúnmila | Divination | Yellow, green |

Table adapted from Miguel "Willie" Ramos, "Afro-Cuban Orisha Worship," in Santería Aesthetics in Contemporary Latin American Art, ed. Arturo Lindsay (Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), pp. 51-76.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Historical Museum of Southern Florida thanks the following individuals and organizations for their contributions to this exhibition.

This exhibition and its programs received major funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support was received from the Miami-Dade County Cultural Affairs Council and the Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners.