I was born on Nov. 5, 1956, in Long Island, New York, to a family of seven kids. My dad is an ex-New York Giant and ex-military from West Point.

We came down to Miami originally in 1975. My first job was at the Castaways as a bellhop. It was up on 163rd Street and Collins Avenue.

I just kind of knocked around Florida for a while and wound up going to culinary school at Florida International University’s school of hospitality here in South Florida. When I came back down for school in late November, I saw Santa Claus in Bermuda shorts and realized I’m not going back up north. I stayed ever since.

Now I’m the general manager of Joe’s Stone Crab restaurant here in Miami Beach, although the Miami Herald once printed my job title as “chief cook and bottle washer.” They printed it, so it’s got to be true.

I started in 1980 as a waiter. In 1982 I was on the door as a seating captain and I was the youngest seating captain ever put on the door. Then I proceeded to be the relief maitre d’. I did the job for a while.

I did leave for two years to take a job running a restaurant in New York City at Rockefeller Center. But I decided I wanted to come back. So when I returned, I started off again as a waiter, then captain, then relief maitre d’. Then I also became a part-time manager. And then, approximately 19 years ago, took on the job as general manager.

Over the years Joe’s has grown. The best way I can explain it is when I first started in 1980, there were 92 employees and we now employ about 400. The operation itself really does get quite busy during season, especially for stone crabs. Stone crab season runs from Oct. 15 to May 15. During the summer months we close the market. And on the restaurant side we do dinner only. This allows our chef and sous chef to play with the menu and be creative with certain food products that are only available fresh during the summer. Our guests and our locals are then able to have something besides crabs and realize Joe’s is not just crabs.

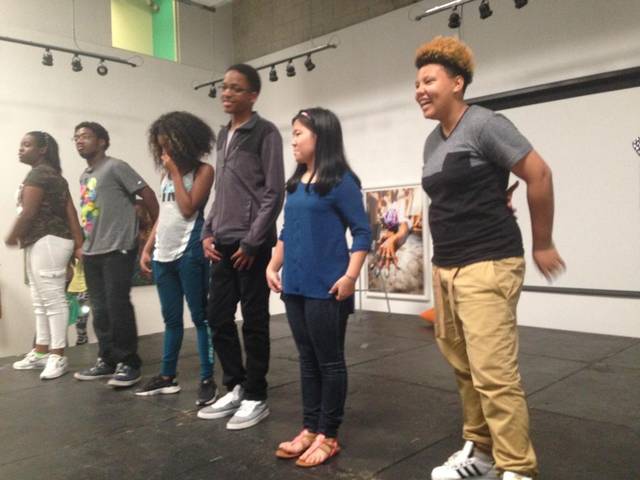

We also have multiple languages spoken on the floor. That’s important, especially in Miami. It’s such a melting pot.

During season I’ve got about three staffers who speak Russian, two who speak Chinese and two who speak Japanese. One of them is a short Italian guy who speaks perfect Japanese. It’s great. Of course we also have a bunch of staff that speak Portuguese, Spanish, German and French. It puts the guests at ease and gives them a better experience.

You need the diversity in this day and age, and in Miami especially because there are so many different nationalities now. Many years ago it was just Spanish. It’s not just Spanish anymore. It’s everything.

The best example I can give of diversity is from a trip I took to Italy eight years ago where I went looking for wine. As I was leaving, I stopped at a gas station going into Florence.

The guy at the station turned around and asked me where I was from in the U.S. I told him Miami Beach, and he goes, “Oh, Joe Stone Crab! South Beach!” The guy said those two words and I was blown away. This was south of Florence in Italy!

There are people who come here that remember coming here with their grandparents. It’s just one of those things that a lot of people identify with Miami Beach. Joe’s is even a year older than Miami Beach. I will see people coming in the door who say they haven’t been here in 40 years.

So we’ve been around here for a little while, and if everything goes right Joe’s will be here for another 100 years.

Miami of years prior was extremely transient. People would come and go. I don’t see that happening anymore. They’re staying planted longer. Miami has grown into more of a business hub. I’m seeing more international business here than I’ve ever seen before, which I think is a great thing.

People come in who don’t really speak English but they’re able to get through it, and they’re enjoying it. That’s what Miami’s about. You’re here to enjoy it.

This story was transcribed from an interview between Brian Johnson, general manager of Joe’s Stone Crab in South Beach and the HistoryMiami South Florida Folklife Center as part of a research project exploring the question “What Makes Miami Miami?” The Florida Folklife Program, a component of the Florida Department of State’s Division of Historical Resources, directed the project.