Long before Coconut Grove’s first high-rise was built at 2951 S. Bayshore Dr., that address was known as The Compound and described by Miami Herald reporter Stephen Trumbull “…a pastoral setting of cottages…occupied by newspaper and news wire service men and women…” and UM professors. The verdant property would become Sailboat Bay Apartments, later The Mutiny Hotel. The heyday of The Compound was mid-1950’s to June of ‘67. A paradigm shift was occurring in Miami and changes at this address reflect historic change to all the city. This fragment of interconnecting history concerns some of The Compound’s residents in a short span of years.

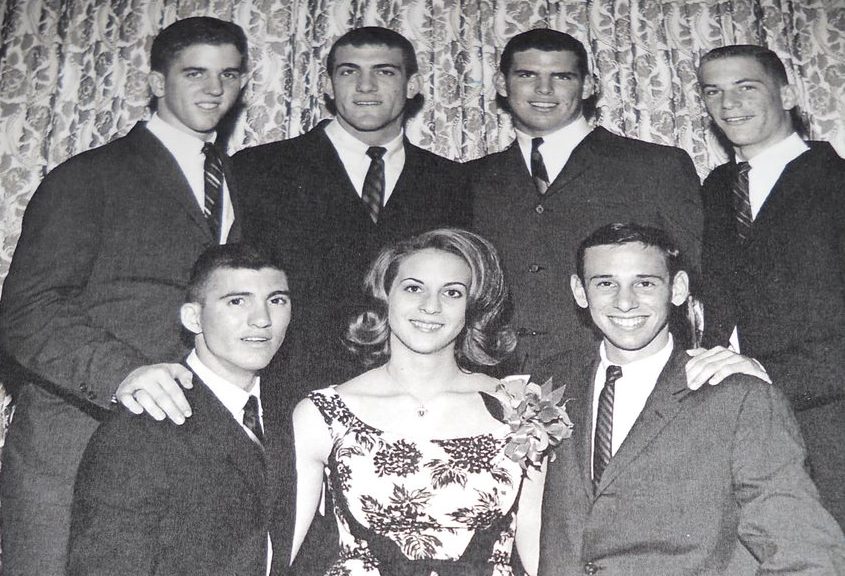

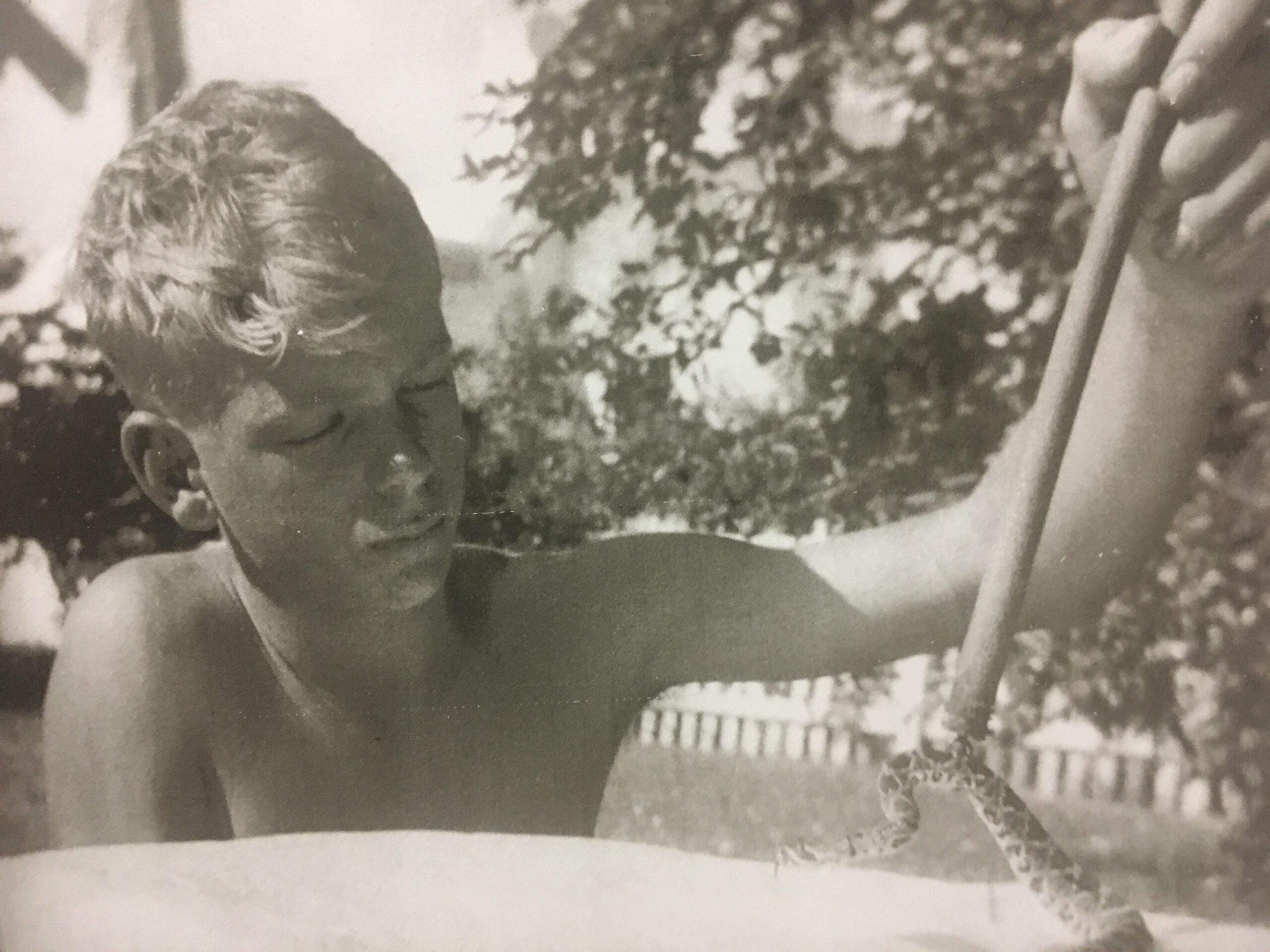

Historic references to The Compound are few, I located some details from Herald stories and research into the life of one of The Compound’s celebrated residents, my aunt, Evelyn DeTardo Hively. By her 1953 Edison graduation, Evelyn had a scholarship to the University of Miami and was a Herald copy boy. By June she was Herald Staff Writer with an article: Evelyn Faces Life reporting on an illegal, pornographic dime peep show. Later she wrote a special series to expose illicit activities behind seemingly innocent ads placed in the Herald, ads offering young women the opportunity to become fashion models but really fronts for prostitution & illegal massage. Evelyn wrote regular columns: Tip Top Teens about outstanding achievements of Miami’s young people and What’s New at the U, events at UM.

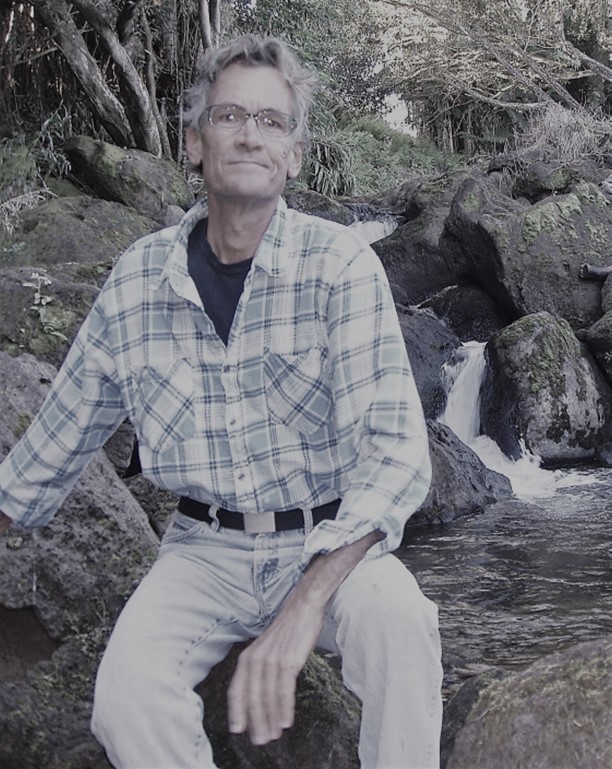

In May of ‘58 the Herald sent her to Haiti to report on Papa Doc Duvalier. Then to Haiti to track down and investigate a witch doctor known for making zombies. She wrote a fullpage zombie story April 12, ‘59. Evelyn was likely the last reporter to interview movie idol Errol Flynn in Miami and Cuba during the revolution filming Cuban Rebel Girls. Evelyn worked at the Herald for 7 years then Time bureau assistant and later professor of English at Miami-Dade College.

Another Compound resident, Denne Petitclerc, had a flair for hooking readers to a story with first lines, “A pair of armed bandits, a bolita bagman, his brunette bookkeeper, a stolen car and an innocent horseplayer flopped up like a school of mullet in a police net Saturday.” Nixon Smiley’s Knights of the Fourth Estate credits Petitclerc for “combining the technique of fiction writing with newspaper writing long before Tom Wolfe & Gay Talese” “he gave readers a glimpse of newspaper writing that would not be seen again until the late ‘60’s.” and “the Herald had become widely known as a newspaper which encouraged individual style and individual writing”. Mr. Petitclerc, like my aunt, was a young, outstanding Herald reporter, among the first to discover the link between Miami, guns and Cuba with investigative reports on the Cuban revolution focused on the underground delivering guns to Castro through Miami. Petitclerc would go on to befriend Hemingway, write novels and write the TV series Then Came Bronson and the screenplay for the feature film Islands in the Stream.

One of my aunt’s best friends at The Compound was Frances Swaebly Herald’s theatre critic. She interviewed stars of the era, Jose Ferrer, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Joe E. Lewis, to name a few, featured in plays and shows in Miami. Reporter Bob Hardin had been living at The Compound after graduating from UM. He, like my aunt, had been writing news for Miami papers since high school. Like my Aunt, he wrote an expose of illicit activities at Miami massage parlors. His series on the Mob’s violent takeover of Miami laundries gained national attention.

For those years The Compound housed creative, talented Herald writers. Other residents of The Compound were United Press International’s Andy Taylor, and Joe Emmert, UM Marine Lab. September 7, ‘62 reporter Stephen Trumbull wrote the Herald story which inspired this History Miami story. Nixon Smiley celebrates Trumbull’s writing style as “salty leads, colorful phraseology likely to take unusual turns.” That’s the case in Intellectual Cats which brings together the residents of The Compound when they decided to round up the stray cats on the property. Surplus cats were products of Crissy being boarded by Bob Hardin & Andy Taylor. She produced innumerable offspring. The Humane Society took many, older cat residents remained.

By June ‘67 Ellen Emmert wrote in the Herald, Grove Progress Means Loss which serves as the Epitaph of The Compound- “the future home of Coconut Grove’s first high rise, Compound residents will be saddened, suffer a small personal loss when bulldozers move in.” From “a pastoral setting of cottages” to Sailboat Bay Apts. to Mutiny Hotel, a big leap. What of those who came before? Late 1920’s to ‘30’s this address, 2951 S. Bayshore, was the place for lavish parties and social events when attorney Leland Hyzer and his wife lived there. These small fragments of Miami history might be lost, forgotten if not pieced together for readers and kept in the archives of HistoryMiami.