Miami, I have seen you grow since 1948. You have become an internationally important city with events that are known worldwide, restaurants with famous chefs, busy highways, theaters with spectacular shows and a mix of cultures.

My first stop in Miami was 64 years ago, 1948, on my way from Colombia, South America, to school in New Jersey. As I walked down the stairs of the propeller airplane, I was surprised to see how tiny the airport was – just a small hangar – but I was impressed with the beautiful ocean and with the stunning white buildings of Miami.

My second trip to Miami was in 1949 when I came to see my parents, who were on their way to Israel. We stayed in a hotel in downtown Miami on Biscayne Boulevard, where we walked the wide avenue and watched the elegant palm trees swaying with the wind. We sat on benches and fed the seagulls and pigeons.

Seeing the ocean in Miami was different from seeing the ocean in Colombia, surrounded by mountains. I returned to school in Carmel, N.J., after my parents left.

My next visit to Miami was in 1952, when my husband, Bob, came on a business trip. I took the opportunity to stay with my uncle Abraham and his American wife, Adele. They lived in a nice neighborhood with impressive shady trees on Pine Tree Drive in Miami Beach.

It was exciting for me because my uncle and aunt took me to the ice cream parlors at the Miami Beach hotels, which in those days were very popular at night. We would go for a snack, for coffee or for one of the splendid ice cream sundaes. The Sans Souci Hotel was their favorite, and I remember the waitresses would pass by with their trays piled high with tall ice cream sodas and sundaes, topped with whipped cream, sparklers or flags.

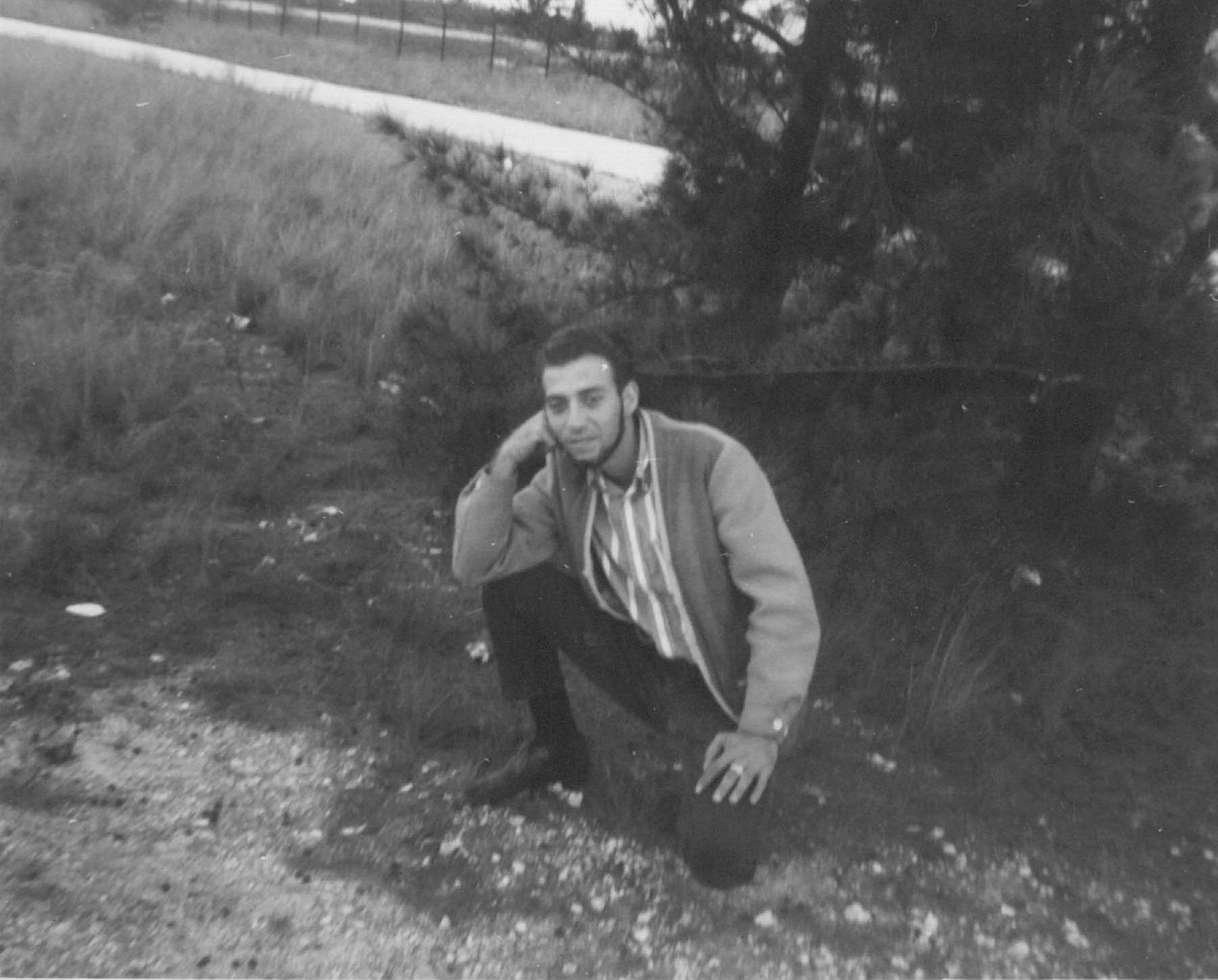

Our son, Alan, was born in Colombia in 1953, and when he was 6 months old, we stopped in Miami on our way to New York. We stayed in a small hotel called the Fairfax, directly across from the ocean because we couldn’t afford oceanfront. It was located on 18th Street near Lincoln Road. I was impressed with its kitchen and diaper service, and the famous restaurant Wolfie’s was nearby.

At night, we would take walks to Lincoln Road, which at the time was lined with very elegant and fancy ladies’ and men’s boutiques, including Saks Fifth Avenue, two cinemas and a European-style drugstore.

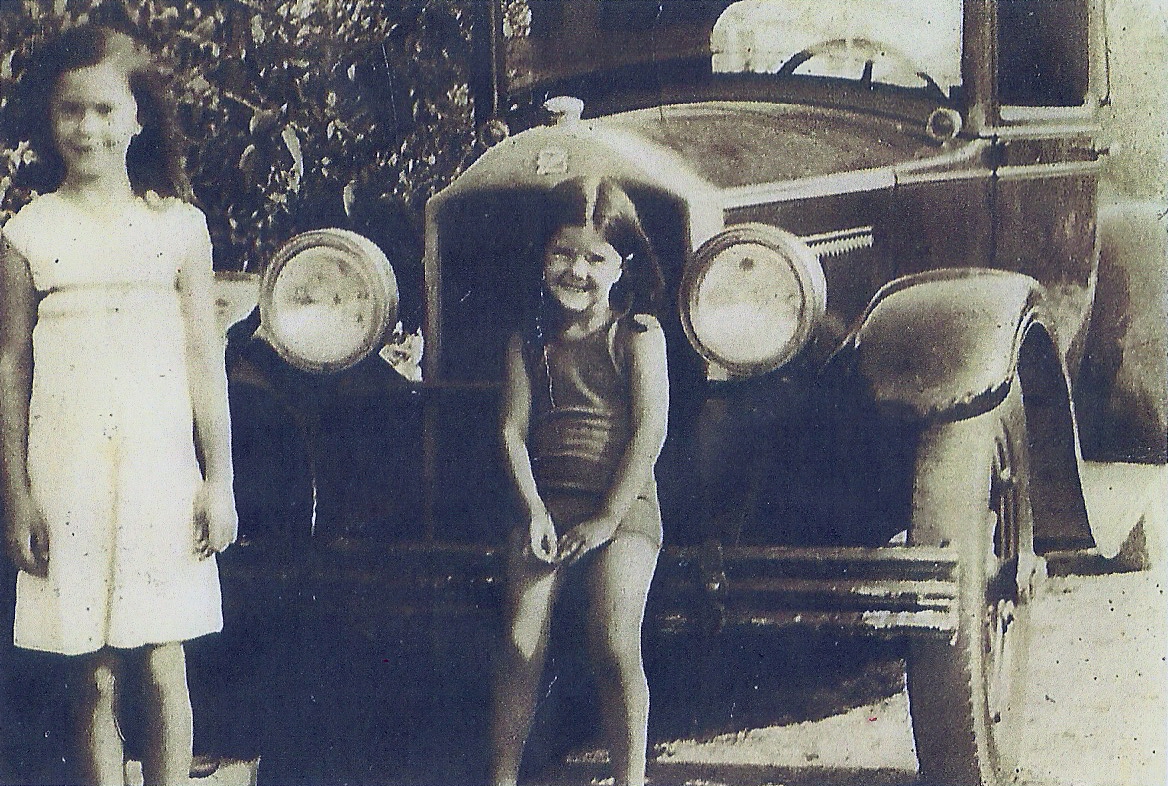

Our fourth trip to Miami was in 1954 and included Bob, our son, Alan, my parents, and Carlina, our nanny. We would swim in the morning and go to Crandon Park, where a little train would take us around; it was one of Miami’s favorite amusements at the time.

Then, during our next trip, we stayed in a hotel on 14th Street called the White House, which was on the ocean and had a wide, white-sand beach with palm trees. By then, we were hooked on Miami, and we came back every year in the summer, taking advantage that our daughters were now in an American school with three months of summer vacation. We found a motel called Beau Rivage, at Collins Avenue and 95th Street, which offered the so-called American Plan, including breakfast and dinner. We stayed in first-floor rooms called lanais, which had sliding doors directly to the pool. This was a great convenience for us, as the kids could easily come in and out whenever they wanted.

The Beau Rivage also had fantastic nighttime activities, like barbecues with hot dogs and hamburgers by the pool and water races for both kids and adults. Back then, Bal Harbour did not exist, and at night we would walk to Surfside to go to one of the drugstores to buy comic books and ice cream.

A few years later, we bought an apartment in Hallandale at the Hemispheres. By then, the kids were grown and going to universities. I recently asked my grown children which Miami memories were their fondest, and, without hesitation, all three children said the Fun Fair, a simple, rustic, open-air park-like place on the 79th Street Causeway. The wooden picnic tables faced an open kitchen where pizza, burgers, hot dogs, corn on the cob soaked in butter, French-fried potatoes, beverages and ice cream were sold.

After dinner, the kids would go inside into an air-conditioned room that had pinball machines, Skee-Ball machines, photo booths and a fortune-teller. We all had grand times there. It was one of Miami’s landmarks.

Miami, now my three children and I have been living here for decades, and we have seen you grow. And as my own family expanded and I became the proud grandmother of six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, we also watched you grow, knowing how lucky we all are to live in this beautiful paradise.