It is unfortunate that nostalgia comes later in life. Having it when memories are fresh might make one more appreciative of what is being lived. I speak of this because of a recent incident that sparked my memories of growing up in the late 1950s through the 1960s in Dade County, on a street just a little north of Perrine and just a little south of South Miami.

My street was an unpaved cul-de-sac that began at U.S. 1 and ran for a couple of blocks. Across the street from my house was a Florida pine forest, though it did not match the forest I would read about in the books I was given in Perrine Elementary school. In those books, leaves fell in the fall and everyone in town would bury potatoes to be roasted with the leaves as they were burned. It sounded like fun to me and it was hard for me to understand why I was not experiencing it in Miami.

The books mentioned snow as well. The good teachers at my school helped give all of us students an idea of what snow was like by having us cut snowflakes out of paper. It was only much later in life that I discovered that our paper models and the real thing in no way matched.

My yard was enormous, or so I remember. It was filled with monarch butterflies, dragon flies, and frogs. Once a year, our yard, the woods, and almost all side streets filled with land crabs. On Old Cutler Road it was not odd to see people collecting them nor was it was unusual see cars with flats caused by them.

The house I lived in was small but made slightly bigger by my father who was very skilled with his hands — something I apparently did not inherit.

A bit north on U.S. 1 there was the Dixie drive-in movie theater, a popular hangout for high school students. Somewhere not far from there was the Miami Serpentarium, a local tourist landmark that was marked by a giant snake statute.

And then there was Harry.

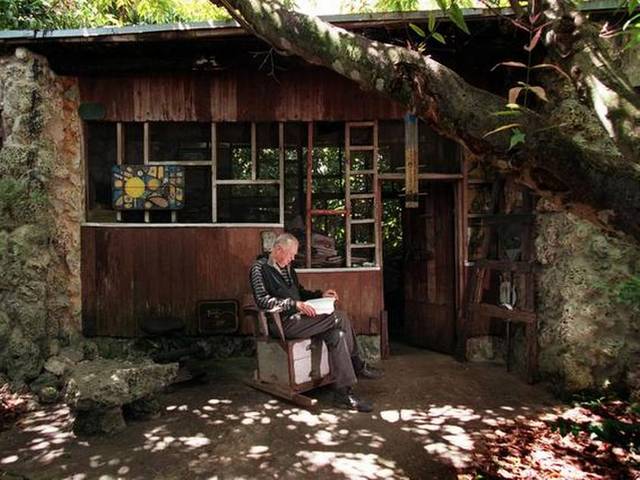

Harry Troeger lived in a small home a few houses down from mine. He designed and built the house. It had no electricity. I suspect he had a well but I do not know for certain. He seemed like a strange man who lived in the small wood and coral house he built. It was almost hidden by trees. For me, my sisters and the other children who lived on the street or the next street over, he was a mystery.

Once a year on Halloween, most of us were brave enough to approach the small house and peek in the windows. We ran like the blazes when we heard a noise. We all assumed the house was haunted.

Harry Troeger, who died in 2008 at the age of 92, was Miami’s Henry Thoreau: a unique man who lived an unusually solitary life in what was, back then, the sticks. Harry was a pioneer.

As a small child I was too timid to say little more than hi when he walked by, heading (I was told) to his job at a movie theater.

Recently, I read in the Miami Herald that his house had been sold to a contractor because of unpaid taxes. The taxes had lapsed in large part because the county was forwarding the bill to an old out-of-date address where Harry lived in the late 1940s.

The article indicated that the house was in danger of being torn down. There was hope, however: it came in the form of a small band of merry Don Quixote types led by Amy Creekmur. The “Friends of Harry” (aka the FOH) were scrambling to make an offer to purchase and save the property.

The lady’s name was familiar. By chance, several weeks earlier, out of curiosity, I checked county records to see who was recorded as the owner of my childhood home. Amy Creekmur had purchased the house I grew up in.

But neither Amy nor the troops that made up FOH were able to move fast enough to save Harry Troeger’s house. His house was brought down. The coral stones he had used for the construction were moved. The wood discarded. A unique part of our local history lost.

It is not reasonable or expected that every old house or historic building be saved. And it is understood that there are many who would save none. To them, the properties are old buildings with no value.

But I believe most of us seek to save some links from our past. Harry Troeger’s house once had historical designation but the agency that granted the status took it away. For me, it is hard to believe that there was a more worthy candidate for continued preservation. Harry Troeger’s house was one of our most vivid links to our past.

I can close my eyes and relive how Dade County was years ago. Sadly losing Harry Troeger’s house takes that ability away from others.

Addendum from the Miami Herald

Troeger built the cabin, which was loosely divided into a wash room, bedroom and reading room, by hand out of coral rock and Dade County pine in 1949. Troeger, who made the cabin his home for nearly 60 years, lived a simple life: no electricity, no car, no running water, only a pump he built himself. The cabin walls were lined with books about Buddhism and works by Emerson.

In 1998, the county deemed the home “unsafe” and threatened to tear it down. When friends and neighbors rallied, the county designated the home as historic and Troeger was allowed to live out his life in his home. In 2008, he died in his bed at age 92.