On the plane ride from Panama to the United States, there was a short layover in Nicaragua. However, we were not allowed to deplane. I looked out the window and asked my mother, “Why are there men with guns outside?” That was my first memory of Nicaragua, where I was born.

The day was Feb. 14, 1985, and I was a precocious 5 year old. I had only heard the stories as my parents spoke with their friends about the events that forced them out of their country. I vaguely knew that the reason we were living in Panama was because of the Sandinistas. It was because of them that my parents were forced to start all over in a different country.

My mother never wanted to go to the United States because she wanted to continue her profession as a professor, which she was able to practice in Panama. In addition, although my father knew how to read and write in English, he saw the United States as a place where he would have to clean toilets, and having been the credit manager of a bank in Nicaragua, he shuddered at the thought. My parents had worked very hard and had overcome many obstacles to become professionals in their country. They wanted more for their children, and that was their main motivation for leaving behind all that they knew.

Under the Sandinista regime, boys would be forced to become part of the military service to defend the “Revolution,” headed by Daniel Ortega, against the counterrevolution, known as “La Contra.” My parents had two boys before me and they refused to allow their children to be used as pawns for something they did not support. So we left for another country without family and without relatives, but where my brothers and I had a chance for a future.

Life always throws curve balls, however, and my brother Lodwin fell sick. My parents took him to doctors and they couldn’t diagnose what was wrong. They took him from specialist to specialist and no one was able to give them a clear answer. After several attempts to take care of the symptoms, the doctors finally came to the conclusion that he had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which spread to his central nervous system and attacked his vision. My 12-year-old big brother had almost completely lost his sight in a matter of a year. The cancer was attacking his body and the only solution that my mother saw was to bring him to Florida and find out what the doctors here could do for him.

My mother was completing her doctorate in education at Universidad de Panama, and we were supposed to be in Miami only temporarily. My father and oldest brother, Richard, stayed behind because they had to continue with our lives in Panama. After all, we were going back once my brother was well. When we walked through customs, I had five dolls. My brother was in a wheelchair wearing dark sunglasses and his lips were cracked and dry; he looked like a skeleton. My mother was strong and swift; she knew what her child needed and she was going to find it here.

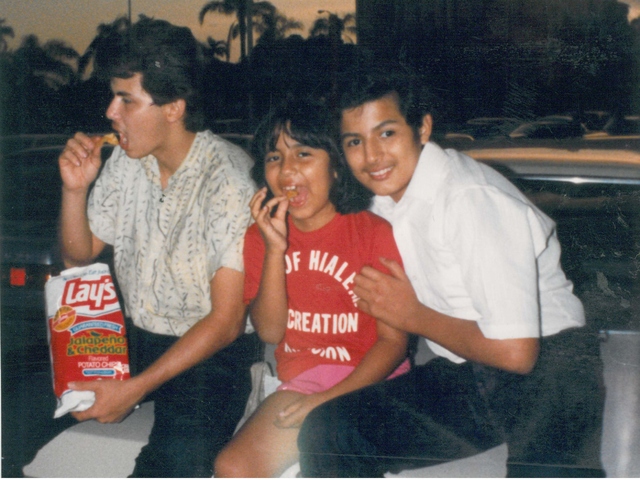

We went to stay at my uncle’s studio apartment off Biscayne Boulevard and 29th Avenue in Miami. My mother slept in a chair and my brother and I slept on a couch. My two uncles slept on the floor. Thankfully, the doctors and nurses in the cancer unit at University of Miami/Jackson’s Holtz Children’s Hospital brought my brother back to life. He went through chemotherapy, and a series of other procedures. Eventually he was in remission, and although he had lost his sight, he was a top student in high school.

We never went back to Panama. Instead my father and eldest brother came to Florida and we all became Americans. We left behind all that we knew. My parents were able to work and grow in different fields, and were able to provide a better future for all their children.

This country gave my brother eight additional years of life. He filled the house with jokes, art, and never complained. My identity revolves around being an American. This country signifies life to me. It brought my brother back to life and it has given me a life that I would not have had in Nicaragua, or Panama, for that matter. I’ve been submerged into this culture and I feel like a tourist when I go back to my place of birth.

Living here, I have had the opportunity to graduate from Florida International University in business, and later had the opportunity to change careers. Here, my political party affiliation doesn’t determine the jobs or promotions I will get. How I feel about President Obama doesn’t determine my future. My children will never be judged by my choices and they will be able to decide their own futures. I have the liberty to grow and achieve what I am willing to work for.

Today, I hold a master’s degree and I teach young people who are very much like me. This melting pot, Miami, exposes us to a “ colada” and “ empanadas” and different ways of saying things in Creole, Spanish, and Portuguese. I have met people who have come from Haiti, Argentina, and Iowa – in one sitting. My students reflect that diversity and that same hope for the future. They have their own immigrant stories and they are here because their parents want a future for them that they cannot have in their own countries. There is no other place like Miami in the world. The United States is a beacon of light, when we have come from such dark paths. I tell them this every day as we salute the flag and “Pledge Allegiance” to it.