Port Royal, Jamaica

February 16, 2007 - June 3, 2007

Online

PORT ROYAL, JAMAICA

An exhibition organized by the Institute of Jamaica and the Historical Museum of Southern Florida (HistoryMiami)

16 February – 3 June 2007 HistoryMiami Museum Miami, Florida

January – June 2008 Institute of Jamaica Kingston, Jamaica

OVERVIEW

From the ‘wickedest city on earth’ to a thriving commercial centre of the New World, Port Royal, Jamaica, has been the subject of much popular interest. While the image of a decadent and lavish city bears some truth, it obscures a more complex history of English colonization and the African slave trade, of skilled craftsmen as well as crafty men, of formidable forts and awesome gunships, of urban devastation and preservation—all of which is part of the story of a town whose sleepy present belies its past of excitement and intrigue.

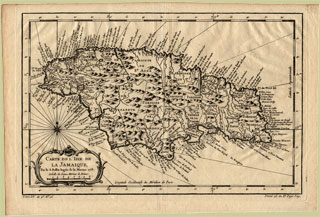

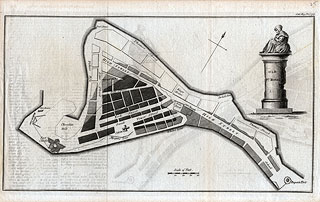

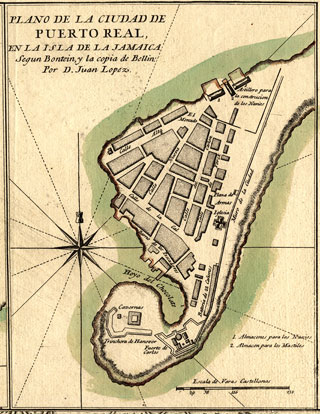

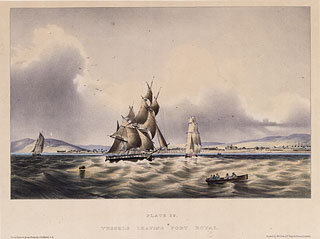

Following England’s conquest of Jamaica from Spain in 1655, Port Royal developed into a major city of the English Americas, comparable in size to Boston. Fuelled by pirate raids on Spanish galleons and ports and a growing plantation economy based on the enslavement of Africans, the city flourished with a wealth of fashionable imported goods and a plenitude of local pewterers, silversmiths, blacksmiths, shipwrights and other tradesmen. This prosperity and glitter suddenly ended on June 7, 1692, when a massive earthquake swept two thirds of the city under the ocean. Port Royal, however, soon re-emerged as a naval base that lasted for two centuries under the command of such celebrated British officers as Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson.

Today, Port Royal lives on as a small maritime community and a heritage site of worldwide significance. Artefacts recovered through underwater and terrestrial archaeology form the basis of this exhibition, with additional perspectives provided by rare maps and prints and documentary photographs. Together, this material reveals Port Royal’s prominence in the history of the Atlantic world.

MARITIME TRADE AND PIRACY

Soon after their arrival in Jamaica in 1655, the English began mounting a defence of Port Royal against recapture by the Spanish. To protect the harbour, they hastily erected Fort Cromwell, which was renamed Fort Charles following the crowning of Charles II in 1660. By the time of the earthquake in 1692, an impressive array of forts and stone lines encircled Port Royal, making it one of the most heavily defended cities in the Caribbean.

In the years immediately following the English conquest, Jamaica remained vulnerable to Spanish attacks. Thus, Governor Edward D’Oyley enticed buccaneers, who were already preying on ships in the region, to occupy Port Royal and provide the city with maritime protection. Since the English government officially commissioned these pirates, they were known as ‘privateers’. The most infamous of the lot, Henry Morgan, was commissioned in 1668 and carried out several spectacular raids against Spanish fleets and ports. Though the Treaty of Madrid between England and Spain in 1670 abolished privateering, the practice continued surreptitiously. After being appointed the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica in 1674, Sir Henry Morgan apparently both suppressed and encouraged privateers.

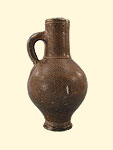

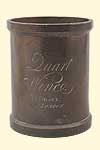

During the 1660s and 1670s, the privateers brought tremendous wealth into Port Royal in the form of Spanish silver, gold and precious stones. This wealth, in turn, allowed the residents of the city to carry out a flourishing trade in European staples and luxury goods—such as wines, sweet meats, refined clothing and jewellery—and to import porcelain from China and ivory from Africa.

TRADESMEN AND THEIR CRAFTS

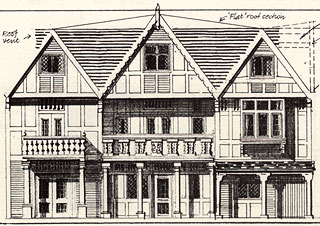

As Port Royal flourished, its cosmopolitan population created a demand for a wide range of tradesmen with specialized skills. Surveyors, architects, engineers, masons, carpenters and blacksmiths constructed the city’s various commercial and public buildings and its many private residences. On the busy docks, there were large numbers of shipwrights and sail-makers who refurbished visiting ships, while wherrymen and porters moved the vast array of goods arriving in the city. Coopers were particularly important, since fresh water had to be transported to the island city in barrels. Coopers also made casks for storing wines, liquors and pickled meats, as well as for the export of dyes, sugar, rum and molasses.

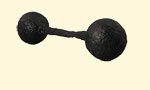

The wealthy Port Royal residents desired the latest fashions in clothing and the finest furnishings for their homes. While many items were imported, the city also supported local seamstresses, cobblers, hat-makers, cabinetmakers, pewterers, silversmiths, goldsmiths and other craftsmen. Among the more remarkable local art forms were intricately engraved comb sets and small boxes, fashioned from tortoiseshell. Gun and sword smiths were also essential in this heavily armed community, while surgeons and druggists attempted to keep the population healthy.

Some of Port Royal’s tradesmen became well known for their high quality products. For example, Simon Benning, a prominent English-born pewterer, operated an establishment in Port Royal from as early as 1667. Although few records remain, both enslaved and free Africans worked in several crafts, including the making of smoking pipes from local red clay.

LIFE IN THE ‘WICKED CITY’

By 1692 Port Royal had an estimated population of 6,500, of whom perhaps 2,500 were enslaved Africans. Many of the white residents of the city were indentured servants. Though a portion of the population lived in great luxury, most survived under much more humble circumstances.

In 1680 there were approximately 1,000 houses in Port Royal, built in a manner that resembled an English town. Large houses were often multi-story brick structures with four-room floor plans. Ground floor rooms that fronted the street were sometimes used for shops or offices. In their private chambers, ladies fussed and primped, received guests and penned letters. A man’s bedchamber, on the other hand, doubled as his office or study—a place to secure money, weapons and books. The splendour of the finest homes was comparable to that of London.

Port Royal was a city of pomp and prestige. Official events were grand displays of the King’s authority with parades and the changing of fort guards to fife and drum bands. While there were lavish balls and banquets, much of Port Royal’s social life revolved around the numerous taverns and included the usual drinking, brawls, smoking, eating and even sleeping. Other activities, considered inappropriate for polite discussion, contributed to the city’s reputation for decadence and wickedness. Though freewheeling, Port Royal was certainly not all wicked. According to observer John Taylor, ‘they allow of a free toleration of all sects’. Indeed, there were Roman Catholics, Presbyterians, Quakers and Jews, along with the Anglican congregations of Christchurch and Saint Paul’s.

1692: THE PORT ROYAL EARTHQUAKE

It was about 11:42 am on Wednesday, June 7, 1692. The residents of Port Royal were retiring home, or to a tavern, for a drink and their main meal when a roar came from the hills across the harbour. Shockwaves had the land suddenly ‘rowling and moving’ and, within minutes, three tremors tore through the ground. The sea swept in from all sides. The earthquake had struck.

An anonymous eyewitness stated: ‘The sand in the street rose like the waves of the sea, lifting up all persons that stood upon it, and immediately dropping down into pits; and at the same instant a flood of water rushed in, throwing down all who were in its way; some were seen catching hold of beams and rafters of houses, others were found in the sand that appeared when the water was drained away, with their legs and arms out’.

By the end, only 25 of Port Royal’s original 60 acres remained. The earthquake claimed approximately 2,000 lives instantly. A further 3,000 succumbed to injury, fever and vandals who fell upon the suffering and dying. One Port Royal resident, a Frenchman named Lewis Galdy, was swallowed up by the earth and subsequently spewed out alive. Most, however, did not have his good fortune.

To many, the calamity was a sign of God’s wrath, His retribution upon this ‘Sodom of the Indies’ with its hosts of reckless filibusters, harlots and moneylenders. Following the earthquake, survivors established Kingston across the harbour but did not abandon Port Royal. The community rebuilt itself, though it continued to be devastated by fires, hurricanes and earthquakes.

THE PORT ROYAL NAVAL STATION

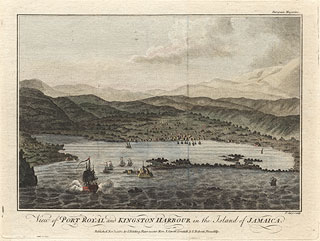

After the 1692 earthquake, Port Royal never regained its status as a vibrant commercial centre. However, it served as the headquarters of the British navy in the Caribbean until the early nineteenth century and remained an important naval base until 1905. From the early 1700s until the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Britain fought numerous battles with Spain and France in a contest over the expansion of empires. Naval forces at Port Royal were under the command of some of Britain’s most illustrious military heroes.

In 1702, during the War of the Spanish Succession, Vice-Admiral John Benbow engaged a French fleet near Colombia; while in 1739, during the War of Jenkins’ Ear, Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon sacked the city of Porto Bello on the Spanish Main. In 1779, in the midst of the North American colonies’ war of independence, a young Horatio Nelson commanded Port Royal’s Fort Charles and prepared for a French invasion. In 1782 Admiral George Rodney defeated a large French fleet in the Battle of the Saints, thus preventing the feared capture of Jamaica. In addition to major military engagements, the British navy at Port Royal continued to pursue pirates in the region and provided transatlantic escorts for ships carrying Jamaica’s massive output of sugar and other plantation commodities.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, various improvements were made to Port Royal’s naval docks, facilities and fortifications. In 1817 work began on a new naval hospital, using pre-fabricated cast-iron beams. This expansive building was famous not only for its modern technology but for its ‘fine air’ and the care provided by African-Jamaican nurses.

PORT ROYAL TODAY

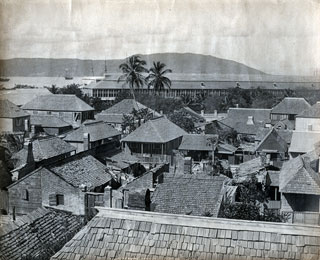

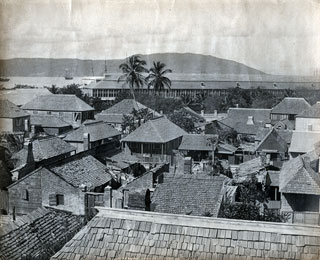

In 1905 Britain closed its naval station at Port Royal. With the withdrawal of this source of employment, the residents of the community were forced to pursue other occupations, such as fishing, fish mongering and ferrying. Some moved across the harbour to Kingston to seek work. Despite these changes, the town maintained its original layout and traditional character, with two and three-story nineteenth-century dwellings, lodging houses, shops and bars huddled together.

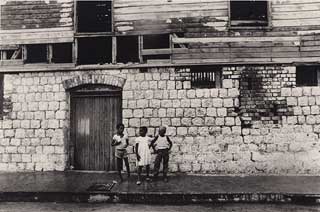

In 1951 Hurricane Charlie wiped out Port Royal, leaving only a few of its wooden buildings standing. The old Naval Hospital, which remained intact, provided a safe home for almost the entire population. Once again, the citizens of Port Royal rebuilt their town. The proud community carried on its daily life, as captured in photographs shot by Maria LaYacona during the 1980s. Surviving buildings of the naval station served as a police academy and small military base and, at present, provide a headquarters for the Jamaica Coast Guard.

Today, Port Royal’s ruins from the 1692 earthquake appear as ghostly silhouettes at the bottom of the shallow murky waters surrounding the existing town. Since the 1950s, myriad artefacts have been recovered through underwater archaeological excavations, though less than 10% of the catastrophic site has been surveyed to date. Whether crushed, mangled, shattered or in pristine condition, these artefacts are evidence of the history of a town that has seen many defeats as well as numerous attempts at rebirth. In 1999 the Jamaica National Heritage Trust designated Port Royal a National Heritage Site. The underwater city is undeniably one the world’s archaeological wonders.

CREDITS

Port Royal, Jamaica was organized by the Institute of Jamaica – Museums of History and Ethnography, and the Historical Museum of Southern Florida; by the kind permission of the Government of Jamaica, through the Ministry of Tourism, Entertainment and Culture. The exhibition includes more than 200 artefacts, maps, prints and photographs from the collections of the Institute of Jamaica, the National Library of Jamaica, the Historical Museum of Southern Florida, the University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries (Special and Area Studies Collections and Map and Imagery Library), the University of Miami Libraries (Special Collections Division), National Geographic Image Collection, Brett Ashmeade-Hawkins and O.J. Cox.

Video was provided by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology / Nautical Archaeology Program at Texas A&M University and the Public Broadcasting Corporation of Jamaica.

Port Royal, Jamaica is sponsored in part by The Miami Herald, ExxonMobil, The Jamaica Committee, Air Jamaica, Jamaica Tourist Board and Jamaica Awareness. Additional support was received from the State of Fla., Dept. of State, Div. of Cultural Affairs, Fla. Arts Council & Div. of Historical Resources; the Miami-Dade County Dept. of Cultural Affairs, the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor & the Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners; and the members of the Historical Museum of Southern Florida.

Special thanks to the Hon. C.P. Ricardo Allicock, Consul General of Jamaica, Miami; the Hon. Aloun N’dombet-Assamba, Minister of Tourism, Entertainment and Culture, Jamaica; Marcia Bullock, Jamaica Tourist Board; Eddy Edwards, Jamaica Awareness; Marlon A. Hill, The Jamaican Diaspora; Cathy Kleinhans, Jampact; Jacky Shepard, The Jamaica Committee; Vicki Silvera and Tina Spiro.

© 2007 The Institute of Jamaica and the Historical Museum of Southern Florida.

Museums of History and Ethnography Institute of Jamaica 10-16 East Street Kingston, Jamaica (876) 922-3795 www.instituteofjamaica.org.jm

Historical Museum of Southern Florida 101 W. Flagler St. Miami, FL 33130 (305) 375-1492 www.hmsf.org